About Utai (Noh chanting)

From the point of view of Western music, in Noh, there is not a set pitch and tempo is not stable.The Noh.com : Vocal

I attach PDF which you can read the score and listen to music. You can see the traditional score of Noh on the left and three lines notation and western notation on the right. Three lines notations indicate the graphic figure of theoretical reading of the traditional score. Western notations indicate how to sound in reality. If you click the button on the top, you can listen to music.

「 indicates roles. 「Shite means the mail role, 「Chorus means that this part is sung by chorus, jiutai. This time Ryoko Aoki sang all roles.

※ In order to listen to sound, you have to download the PDF file and view them through Acrobat Reader.

Utai (Noh chanting)

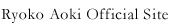

Some lines are performed to musical accompaniment, and some are not. The words of a chant are called kotoba and the music is fushi. Both actors and chorus chant.

"Hagoromo" Kanzeryu-Taiseiban, Hinoki-shoten, Tokyo

Kotoba (words)

The nonmetered, nonrythmical "words" or prose portions spoken by actors.

No notation is provided for the prose passages.

"Hagoromo" Kotoba

Kanzeryu-Taiseiban, Hinoki-shoten, Tokyo

Fushi (melody)

The metered chanting (utai) of the actors or chorus (jiutai). Texts are marked with special dots, curved, and angular markings and Japanese syllables that indicate a variety of vocal and rhythmic requirements, but can only be used as guides to what the student has learned by heart and what he understands of the character's nature.

Fushi (melody)・・・Yowagin, Tsuyogin

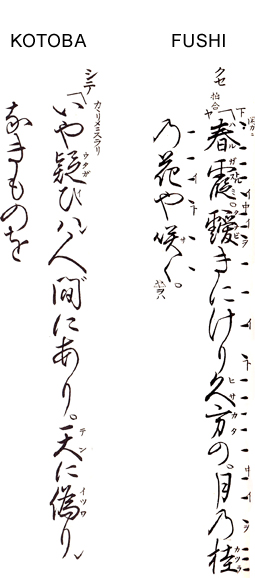

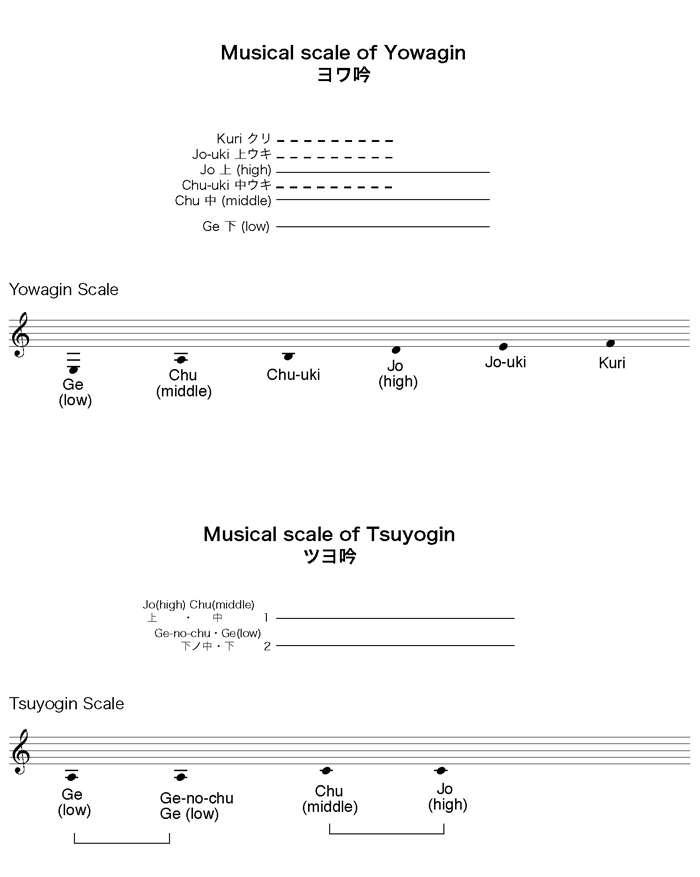

Yowagin

"Weak singing", a fundamental mode of Noh chanting capable of being transcribed to a Western staff, and used to express pathos or elegance. It is contrasted with tsuyogin in having a distinct melody and subtle emotion. It is best suited to the Third Group. There are plays that are entirely in yowagin but it is more likely for yowagin and tsuyogin to be mixed.

Tsuyogin

The "dynamic mode chanting" method in Noh used to express boldness, excitement, or profound emotion. It is much less melodic than its counterpart, yowagin. Rhythm is privileged over melody, and it has a narrow pitch range, varying more through levels of intensity than through melodic range. It did not appear in early Noh and was first introduced during the Genroku period; the version heard today dates from the mid- to late 19th century. It is heard mainly throughout the First Group, in the kiri part of the Second Group, and in the second half of the Fifth Group. Some plays are chanted entirely in tsuyogin while others mingle it with yowagin.

Musical scale of Noh chanting

In Noh, performers are not required to sing with the certain pitch. It does not matter if they sing a bit higher or lower than last time (but not bigger difference). But the between musical intervals are always same. This is the musical scale of Ryoko Aoki.

The rules of Fushi (melody)

・Yawagin

The rules of Yawagin Fushi (melody)

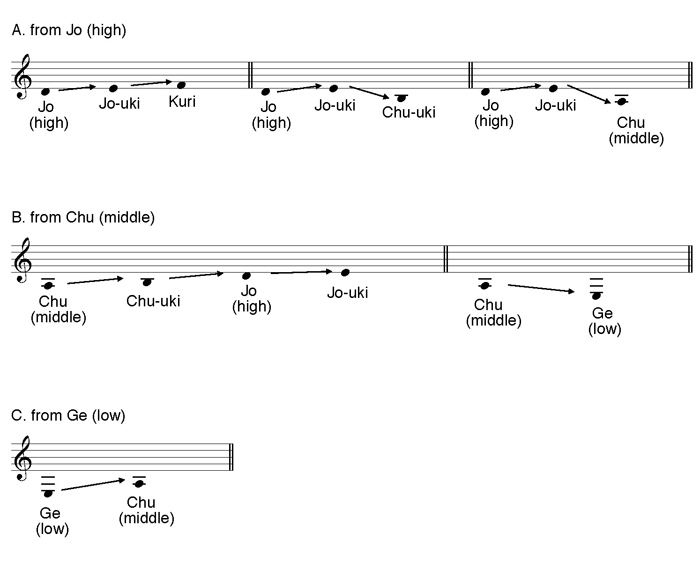

- The melody line should fall from upper pitch to middle pitch, and from middle pitch to lower pitch. It should rise from lower pitch to middle pitch, and from middle pitch to upper pitch. It never falls from upper pitch to lower pitch directly and never rises from lower pitch to upper pitch directly.

- When the melody falls from upper pitch to middle pitch, it should rise from upper pitch to a bit higher pitch, and then fall to middle pitch. When the melody rises from middle pitch to upper pitch, it should go through the middle between upper pitch and middle pitch, and then to upper pitch.

- The melody can fall and rise between middle pitch and lower pitch directly.

"Tomoe" Shidai Koichi Miyaka "Fushi-no-seikai" 1990, Hinoki-shoten, Tokyo

The rules of Tsuyogin Fushi (melody)

Yowagin..... Jô 上 (upper pitch), Chû 中 (middle pitch), Ge 下 (lower pitch)

Tsuyogin..... Jô 上(upper pitch), Chû 中(middle pitch), Ge-no-chû 下ノ中 (middle between middle and lower pitches), Ge 下 (lower pitch)

But in Tsuyogin, Jô 上and Chû 中are the same pitch and Ge-no-chû 下ノ中and Ge 下are the same pitch.

I indicated 1 (Jô 上and Chû 中) and 2 (Ge-no-chû 下ノ中and Ge 下) in the example.

Kosode-soga" Shidai Koichi Miyaka "Fushi-no-seikai" 1990, Hinoki-shoten, Tokyo

※ The example "Chikubushima"

Normally a part of "Chikubushima" is sung in Yowagin, but here just as an example, I sang a same part in Tsuyogin to compare the difference.

"Chikubushima" Yowagin (Original version) Kanzeryu-Taiseiban, Hinoki-shoten, Tokyo

"Chikubushima" Tsuyoagin (It does not exist in traditional Noh)

Rhythm

Here I explain the rhythm of Noh when performers sing with Noh instruments. So, if performers sing alone, it sometimes does not apply.

Noh chanting employs traditional, non-metronomic rhythms (nori), divide into hiranori ("flat rhythm"), chunori ("middle rhythm"), and ônori ("large rhythm"), the first being the most common. In it, the 12 syllables of the seven-five shichigocho meter are spread over eight beats (hachi byoshi); the feeling is like that of reading waka poetry. Chunori (heard after the departure of a ghost or spirit appears) has 16 beats for the 12 syllables. When a passage is to be chanted to a specific rhythm, it is hyoshi ni au ("keeping time"); the opposite, when the chanting is noncongruent with the percussinon, is hyoshi ni awazu ("not keeping time"). Although the latter is freer, it too must conform to strict conventions.

Hyoshi ni awazu ("not keeping time")

"Hagoromo" Hyoshi ni awazu

Kanzeryu-Taiseiban, Hinoki-shoten, Tokyo

Hyoshi ni au ("keeping time")

- Hiranori ("flat rhythm")

"Hagoromo" Kuse

Kanzeryu-Taiseiban, Hinoki-shoten, Tokyo - Chunori ("middle rhythm")

"Kiyotsune" Kiri

Kanzeryu-Taiseiban, Hinoki-shoten, Tokyo - Onori ("large rhythm")

"Hagoromo" Kiri

Kanzeryu-Taiseiban, Hinoki-shoten, Tokyo